“Some folks are all about the business, while others are all about the art – and in both cases, it’s sometimes to their detriment. Me, I don’t like drama. All I do is play my guitar and sing a few songs, because that’s what I’ve always done, and that’s what I’ll always do. I don’t get caught up in whose record has sold more copies or who did this first, or who plays better than this guy, that guy, or the other guy. I leave all that other stuff up to everybody else.”

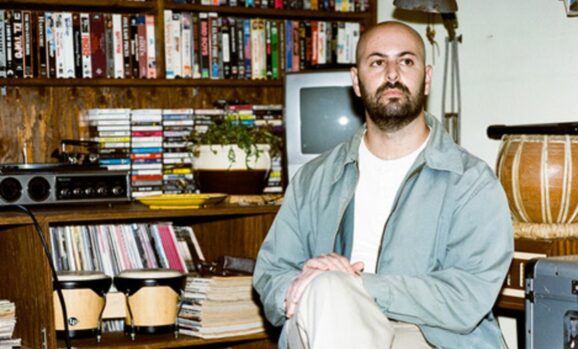

The great Jazz R&B artist George Benson never wrote more truer words about himself than those in his 2014 autobiography, Benson. Eternally humble, always gracious, with a keen instinctive musical mind, he has stood strong from his beginnings in Pittsburgh to the lights of Hollywood, New York and beyond. He is respected, has earned more awards than the day is long, has performed with the elite of the music business, and now he is about to share his knowledge and skills with his first-ever Breezin’ With The Stars event.

A lot of musicians participate in master classes and retreats for everyday players, sharing with them what they, as longtime professional artists, have learned after many years of good, bad, and ugly. It is their gift to the like-minded who may or may not want to follow in the footprints they have laid down. To be held in Phoenix, Arizona, from January 3rd to the 6th, 2025, it will encompass everything from Q&A’s to jam sessions with lots of learning in-between, with guests such as Toto’s Steve Lukather, Lee Ritenour, Tommy Emmanuel, Esperanza Spalding, Andy Timmons, Stanley Jordan and others. [You can find out more information on tickets and the event itself here https://breezinwiththestars.com/] It is something Benson is very much looking forward to. “I’m going to learn quite a bit too,” he told me during our recent interview.

Whether you are a fan of soul, Jazz, R&B, rock & roll, folk or just smooth vocals with funky rhythms, the name George Benson has somehow passed by your musical atmosphere. He started on the ukulele when he was a small kid, switched to guitar, played in clubs before he hit double-digits in age, and before long, he hooked up with the Jack McDuff Band, where he learned to listen and absorb other artists. “When you hear something that touches you,” Benson wrote in his memoir, “learn it, absorb it, then make it your own. The number of Wes Montgomery solos I’ve listened to over the past fifty years can’t be counted, so he’s in my DNA – and my fingers for that matter – but even when I’m not covering one of his tunes, Wes is along for the ride.” Albums started happening, tours, special appearances with major stars; and then Quincy Jones broke him wide-open in 1980 with Give Me The Night, which charted in the Top 10 worldwide and earned him three more Grammys to add alongside the four he’d already won.

At 81, Benson is considered a legend in music – not just Jazz or R&B. He has spawned hits and accolades, more than he himself can count, and yet he still loves learning and listening and creating. Although his latest album, Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon, began in 1989 and was abandoned due to record company bullshit, it’s now been tweaked by Benson and released. Full of beautiful songs that fit his voice like satin honey, it’s a shame they sat quiet for so long. His version of “Song For You,” written by Leon Russell, alone is worth it’s weight in gold; add in “Yesterday,” “At Last” and “My Romance,” and you’re floating on dreams.

Before we get to my quick chat with the man himself, I do want to throw out these couple of tunes you should listen to as soon as you finish reading: “Sweet Alice Blues,” “Giblet Gravy” and on YouTube his performance from the 1966 Newport Jazz Festival. All from early in his career but show his prowess as a guitar player, especially the latter.

From his home in Phoenix, Benson shared with me stories from his youth, details about his upcoming event, and what makes a song beautiful.

Where are you at today, may I ask?

I am in Phoenix, Arizona. I’ve been there for many years. I love this place. Sunshine is my favorite thing.

You grew up in Pittsburgh, you live in Phoenix and you’ve been all over the world. When you were a little boy playing in the streets like all the other little kids in your neighborhood, did you ever imagine being anywhere but that neighborhood?

No, I never imagined being anywhere and I’d never even heard of Phoenix (laughs). As a matter of fact, people were telling me that I ain’t going to get anywhere until I went to New York, but New York was about four hundred miles from us. “You can’t make it here in Pittsburgh. There’s nothing here in Pittsburgh!” I thought Pittsburgh had a lot growing up. But not in the music world. There was a lot of music coming THROUGH there, and musicians came through there all the time because they were on their way to New York, and they had that great new turnpike called the Pennsylvania Turnpike. It was a three hundred mile stretch straight to New York from Pittsburgh. So they had to come through Pittsburgh. So they’d stop in Pittsburgh and have jam sessions with people who are now some of the greatest names in Pittsburgh – Billy Eckstine and Lena Horne and people like that, Art Blakey on drums, just great musicians. So I grew up with that. They were grown when I was a little boy but I heard those names on jukeboxes all my life.

Did New York end up being your goal eventually as well?

For me, people said that’s where you had to go. That was it. That was like going to Hollywood, California, on the west coast. New York made more movies than they did in Los Angeles, California, but people didn’t know that then (laughs). So when I got to New York, I finally hooked up with the biggest record company in the world, RCA Victor, and I cut my first record. It didn’t sell any big records or anything, and it never got famous outside of Pittsburgh. I was ten years old, but I was very popular in my hometown (laughs).

But my mother didn’t like what it did to my life because I couldn’t live like a kid anymore. Now I know that happened with Michael Jackson and a few others. They lost their childhood because music snatched them up into the entertainment world, which was vicious from a lot of different points of view. You couldn’t be that innocent kid that you grew up with trusting everybody and just living your life, you know.

So my mother saw that when I was a little boy. My manager was going to take me to California to make me a movie star and she said, “No, not my Georgie. You’re not going to take my son to California.” So she stopped it all right there. So I went back to school and acting like the rest of the kids. And I think it was the right thing to do.

So would you say it was your mother who has always been in the back of your head keeping you grounded and humble all these years?

She was the one who gave me my way of looking at life. When I was a little boy, I used to have trouble with people, you know, getting along with people. She said, “Are you approachable? Can somebody approach you and talk to you about something? Or are you mad all the time about something? People are afraid to talk to you.” I thought about that, and that was the answer. When I loosened up, they loosened up, and I finally had friends. My whole life has been about being approachable. She taught me that and about music. She took me to all of those musicals back then. A lot of great singers back then, and I saw probably all of that stuff, and that stayed in my mind my whole life, those movies, and when I went to school, they called me up on stage to sing or to participate in every event that came along so I got used to doing that (laughs).

In January, you’re going to be sharing your knowledge and your skills with others at your Breezin’ With The Stars. What do you hope these people will learn from you?

Some people, they look to me for many things that I’m not really capable of doing. I’m not a musical scholar but when I hear a song, I know instantly what should be done to make it better. That’s been my legacy in life. When I heard “On Broadway,” I knew why I couldn’t do it the way the original was done. My managers hated that cause they wanted me to do it exactly like the original. I said, “No, that’s already been done. Why are we doing that for?” So I’d take the song and do something else with it, you know. And “Breezin’” was the same way. I had heard the original version of “Breezin’” and I said, “That’s a nice version, leave it alone, you can’t improve on that. That’s the way it sounds. But let me work with it.” And I did and it came out a smash.

“This Masquerade,” when I heard Leon Russell singing it, I said, “It ain’t going to get better than that. What do you want me to do with it?” The manager said, “People would like to hear you sing it.” I said, why (laughs). So I said, “Okay, let me do something with it.” We put it on and started doing the do-da and putting the guitar and singing with it. They didn’t think it would work at first. “That’s no good.” I remember the first time I tried that the producer said, “That’s no good, let’s cut this short and go to something else.” So you never know where life is going to lead you but go, get some experiences.

So you’ll be playing guitar at your event and putting on a show?

I don’t really know. I got some great musicians who are going to be there for the event so something tells me that we’re going to get involved (laughs). I’m always open for everything cause you don’t know what’s going to happen next. That’s what life is all about, different inspirations make you think differently.

But I have worked with them before, maybe a couple of Japanese names I know them but I don’t think we’ve worked together but I look forward to working with them because I know their musicianship is outstanding. So yeah, I’m looking forward to all of that stuff. I’m going to learn quite a bit too (laughs). I’m not going to call it stealing; we’ll call it borrowing. I will borrow what I’m going to sing to (laughs).

Dreams Do Come True, your rediscovered album, has such beautiful songs on it and you finally got to put it out.

Well, I asked the great Quincy Jones, “Who is the baddest cat? Who is the greatest arranger in the world?” I thought he was going to say, “Me! I’m the baddest.” (laughs). I didn’t really think that cause he’s not that kind of guy. But anyway, he came up with a name I had never heard. He said, “George, for you it’s one of two names. I think this man Robert Farnon is the man you want.” So I found Robert Farnon, who was living in London, and I was over there doing a concert and I looked for him and I found him and he agreed to write and he wrote seventeen arrangements for me. I think we recorded about, no, we recorded all seventeen, cause we did it in a couple of days in a gigantic studio that held eighty-seven musicians. They borrowed them from the London Symphony Orchestra. And it was quite the day. I was amazed and mesmerized. I said, I could never live up to this music. But I’m going to take it with me and try it. I took it to New York and the songs that we didn’t finish in the studio, I worked on them. And boy did some wonderful sounds come in my head. I just was so glad I had done that. Unfortunately, the record company said, “No, we like you just the way you are, George. We like those hit records you coming up with. We don’t want anything new.” (laughs)

So I put it up and thirty years later they called me and said, “We got this stuff here and they want us to throw it out.” I said, “Don’t throw nothing out until you tell me what it is.” They said, “Robert Farnon,” and I said, “Oh man, I wondered what happened to that stuff.” So they sent it to me on an 18-wheel truck, that’s how much stuff it was they sent me from my warehouse. I whittled through the stuff and I found those tapes. Man, I couldn’t believe what was there. So we started there.

To you, what makes a song beautiful?

Songs are nothing but musical expressions of people’s thoughts. It’s like a language, you know, but if you’re talking to somebody you want them to get the point, you want them to get the whole point and not just partial. Everybody speaks English but not everybody speaks English with a conviction; not everybody speaks it with a great diction. Sometimes you like the slang that people have when they talk, you know. So all of that comes into play: What kind of song is this? Is this a song you should sing straight up and down? Or do you want to add some funky to it? Or some pop to it? What is it? So that is the kind of thing that goes through my mind. My mind knows automatically, it seems, what to do with a song when I hear a song. If somebody was singing this to me, how would I want them to tell this to me? And that’s the way I project it out from my point of view.

When you first started learning to play a real guitar, cause you started on ukulele, what was the hardest thing for you to get the hang of?

I had small hands cause I was a little kid when I started playing and that’s why I was playing the ukulele, cause I didn’t have enough fingers to stretch across the guitar neck (laughs). So when I was ten years old, or nine years old actually, my mother and father bought me a guitar for Christmas, a little cheap instrument that kept cutting my fingers up cause of the strings. They kept sticking me in the finger and it taught me a technique that I use today. I play very light with my left hand and it gives me a lot of staccato in my playing. One thing that staccato does is you got to be fast because before you get finished with the note, you’re off of the note. You can’t be suspended in air, you got to put something in there. So I started playing fast notes (laughs) and that took me to another place in my career.

You were building a career in the sixties when there was a lot of tension happening around you in the world – the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights demonstrations, the assassinations. Did you let that affect you?

I didn’t. Because of my religion, I didn’t get tied into any of that stuff cause I knew me as an individual wasn’t going to change nothing to any real degree. The world going to be what it was or what it is today. There is no one guy going to turn this into something wonderful. It’s not going to happen, cause when that one goes the devil finds another way to get mankind to hate each other, you know. So I realized that at a young age and I stopped trying to do that. Let me just do what I do. I’m going to sing a little Georgie Benson song, I play a little ukulele and guitar and let me do that. People seem to like that and they started paying me to do that. I said, “So you’re going to pay me?” (laughs) “Yeah, man, we’ll pay you to come down and do this in our building, this school or church.” In the beginning it was churches and I didn’t stay with that long.

You went towards Jazz but you could have easily gone straight blues with your playing. Why didn’t you?

When I was a little boy, I grew up in the ghetto and the ghetto was full of different kinds of people. They had a lot of Italians and a lot of Irish people and so forth and so on, so it was a multi-racial neighborhood; a lot of Jewish people in the neighborhood. So we learned a lot of things from different angles, but you learned it from your neighbors. Some of them were kind and some of them were not. We learned who to stay away from and who to make friends with. But I started selling newspapers when I was seven years old. In my whole life, I sold one newspaper (laughs). As I was selling newspapers, I had to go to the bars and I was a little boy, I was only seven, so the jukebox speaker was almost right at my ear as I walked through the bars. I’d holler out and they couldn’t hear me. “Would you like a newspaper?” They didn’t hear me. They’d walk by me like I didn’t exist and bang me all around the room with their knees cause they didn’t know I was there (laughs).

So one guy, he said, “Hey,” he hollered at me from across the street as I came out of one of those bars. “Say little boy, gimme one of those papers, son.” And I was so happy I didn’t know what to do. Remember, we only got a penny and a half for every newspaper we sold. Newspaper sold for five cents so we got a penny and a half for that. When he bought the paper, I remember crying cause he had a quarter and I couldn’t give him any change. “That’s alright, keep the change.” I said, “Keep the change?” That’s more money than I would have made if I had sold all seven papers.

So I took the papers back and turned in the papers I had and I went to a drug store or confectionary store next door and I saw all this candy. I was looking up at all this candy and a guy came up to me, cause now I had my ukulele with me, cause I had given it to the newsstand guy to hold for me while I sold papers. So I was at this drug store buying this candy and a guy walked up, “Hey little boy, can you play that thing?” And I turned around and strummed that thing and folks crowded around, everybody in the place crowded around me. I only got two hands so I couldn’t play the guitar and count money at the same time (laughs) and my cousin walked in and he took off his baseball cap and went around the audience and collected money. That was my first manager, I guess (laughs).

But in the jukeboxes they were playing blues mostly. They used to sing them like their long lost soul. It was very popular but every now and then I’d hear something incredible. I heard Nat Cole sing (singing) “Chestnuts roasting on an open fire.” Not that song then cause that was too early but his songs would come on and he sang some very pretty songs. And when I heard his voice, I said, who is that? I found out his name and I said, that is the kind of songs I like. It had a story, you see. In blues, the first two lines were always sung two times: (singing), “Well, my mama loves me and I love my mama too.” Then the next verse was, “Well, I love my mama, I love my mama too.” The same thing over and over and I didn’t like that. I liked Nat Cole when he sang, (singing) “Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa, men have named you.” A story, you know. (singing) “You’re so like the lady with the mystic smile.” Man, that is the way I want to sing.

So I grew up under that influence. But that was slightly Jazz influence cause Nat Cole was considered a Jazz piano player even though he was very popular singing pop tunes. He had that great voice to go along with it. Then I heard Charlie Parker, the biggest influence in my whole life was Charlie Parker. I didn’t believe anybody could play an instrument and make me feel it like that. It was better than anybody’s talking. You couldn’t tell me a story that sounded better to me than Charlie Parker playing “Just Friends.” When I heard that I said, nobody will ever beat that and I don’t think anybody ever did. It was great.

Portraits by Matt Furman; live photo by Leslie Michele Derrough